Finally Peter has handed over to our Closing Plenary by Clifford Lynch, Director of the Coalition for Networked Information (CNI).

Finally Peter has handed over to our Closing Plenary by Clifford Lynch, Director of the Coalition for Networked Information (CNI).Clifford arrived this morning and has been able to attend some very useful Round Table sessions and he's been reading up on the previous sessions so there will be some reflections on what's been said in the last few days in his talk.

Cliff opened by saying that, as some of us will know, he conducted a low profile reconnaissance of the scene here about 10 days ago: one of the things I learned was that edinburgh has been a hot bed of repository development since the 18th century.

If you go to the records office you can get a copy of a document about the building of General Register House called "A proper repository"!

If you go to the records office you can get a copy of a document about the building of General Register House called "A proper repository"!Today I want to talk about four major areas at length:

- Repository services

- Repository services in the broader ecosystem. I think we are also challenged to understand the scope and ambitions of what we call repositories

- Repositories and the life-cycle of what goes in repositories. There are some interesting questions there that we're probably not thinking about quite enough.

- And finally I wanted to talk about selling or building support for repositories. It's not really the right heading. Some of the things I want to talk about are support, some are about the purpose of repositories and there are some other thoughts in there.

Repository Services

One of the things I found so interesting about the discussions this morning has been the distinction that many people seem to be making between data repositories and what they call repositories of scholarly outputs, e-prints or similar terms. They are perceived, with some justice, to have some different characteristics and behaviors. You could spend a lot creating a much wider repository than you would ever need to for an e-print repository: people just can't write that fast. But when you get other types of data in there the storage is consumed rapidly and you hit real policy issues about curation and the rationing of storage.

I think in the States people often think that a repository can do everything. It's interesting to me to turn it around and talk about e-print repository services, data repository services: essentially thinking of suites of services rather than the underlying implementation, servers, storage etc. You get a very different view of needs when you see it that way. When you look at data we may see repositories that range from generic data to repositories that deal with specific genres of data in particular areas. We already see some of the latter in subject repositories. In molecular biology for instance most of the repositories just take very very specific types of objects in specific formats that are disciplinary in nature. Stressing the emphasis on services here is quite helpful.

Repositories in the Ecosystem

Let me say a bit about repository services as part of a bigger and much more complex ecosystem. There was an International Repositories Workshop that JISC and others sponsored in March in Amsterdam that got into this a little. Repositories connect to things that provide support for e-science, workflow management, high performance storage and computing, etc. What we have to be thoughtful and careful about is the scope of what goes on in a repository. I've seen people say that we should put repositories in the workflow for e-science. I've seen put them in the context of high volume, high reliability storage. I'm not sure we want our repositories to be that volatile. I'm sure that there is a space for lots of high quality storage facilities to support academia doing IT-enabled work. But is the space for repositories? Finding the boundaries will be very delicate and very messy.

Also as we put more kinds of things in repositories we have to look at how much of a use or computational environment that repository becomes.

For example what happens if you want to put video in a repository. If I have a big video file I can deposit it into a conventional repository and I can take it out of the repository and use whatever tools I have to view it. On the other hand I might deposit it into a smart video repository that will fix the format, calculate the bandwidth needed to view (and perhaps adjust the format of delivery according to users' bandwidth). That would be a complex repository tailored to the types of objects deposited.

But what about objects like videogames? Do we embed a videogame environment in the repository or do we leave it to the user. These issues have a lot of implications about the development and ongoing support costs of repositories. As we put in data or e-prints in to repositories we have to work out how much computational work you can do in the repository. Can you do complex or only basic computational work? Or do you take data out to do computational work on materials? These issues get at how you build interfaces, how semantic they are, how flexible are they.

Replication and the semantics of replication we are currently very sloppy about. We have rule-based processes about submissions for instance and the idea of propagating multiple repositories - this seems sensible and reasonable. We also know replicated geographically distributed storage is a good thing. We have a suspiciion that not going it alone on storage is a good thing - it's better to share and collaborate in preservation and curation. How replication for reliability and propogation to multiple collections will work still needs a lot of work, similarly provenence and version tracking. This is an area that requires some proper consideration. There is also an issue of storage and the cloud.

Replication and the semantics of replication we are currently very sloppy about. We have rule-based processes about submissions for instance and the idea of propagating multiple repositories - this seems sensible and reasonable. We also know replicated geographically distributed storage is a good thing. We have a suspiciion that not going it alone on storage is a good thing - it's better to share and collaborate in preservation and curation. How replication for reliability and propogation to multiple collections will work still needs a lot of work, similarly provenence and version tracking. This is an area that requires some proper consideration. There is also an issue of storage and the cloud.Further there is the issue of software. People seem comfortable with the concept that software has a place of some sort in repositories, but if we think of repositories in the wider information ecosystems, people have been thinking about replication and preservation already. Software designers have their own repositories of codes and versions and it's unclear to me how our repositories relate to these.

The last ecosystem point I want to make - and it was discussed at some length in a round table earlier - is how we connect repositories and especially institutional, but also disciplinary, repositories into the new name environment that is emerging. From publishers, web of science, journals etc. You have a number of identity management and federation changes that all result in IDs being created. All of these things are at play here. Essentially IRs set you up for the challenge of doing name authority for your local community, but in the context of things like identity management.

One of the fascinating byproduct things we found in a recent workshop was that institutions view your name as being your name according to humans and payroll services. That name may change occassionaly. They have not gone as far as saying that names may not be in roman characters anymore - that what appears in roman characters could just be an extra name version or transliteration of their name (the original may be chinese characters for instance). There is some capacity for name change aliases but it hasn't occured that people publish under versions of their name that may not be what is on their paycheck. People are not always consistent and there is little provision for "literary names" in university identity management. We'll regret that soon if not already. We need to think big about names. I am becoming more and more convinced that personal names are a really important part of scholarly infrastructure and we'll see some fascinating convergence of geneology databases and ID databases into review and scholarly literature. We have the strong compotent of faculty biographies that are linked to scholarly work already and all of that integrates into giant biographical and factual networks. I use factual to differentiate from mental state and influences. I mean the dull facts like jobs held, papers written, very factual sorts of data. I think there's a really big set of developments here that connect into repositories. It would be very helpful to sit back and think hard about this.

There's one other spanning service that we talked a little about in the grand challenge session. And theat's the issue of annotation and annotation of information resources across data and repositories. Herbert Van de Somple has got funding to work on this lately and Zotero is doing some interesting work here. There will be some interesting findings to tie into scholarly dialogue.

Repositories and the life-cycle of what goes into repositories

Repositories and the life-cycle of what goes into repositoriesRepositories to date have been about getting stuff in, making it accessible. We are not far in enough for stewardship and preservation and management of what is in there to be our major concern but it is important that we don't forget about these. It will be important over time. So for example how much specific disciplinary knowledge do you need to classify a specific scholarly knowledge? The depositor knew and understood these things. If there is a serious issue the user can contact the depositor. Short term that's fine. Very long term the contributor may be dead. You may have to make assessments of whether it's worth keeping the data set in light of subsequent developments. You may have to look at formatting and presentation and linking of data depending on what else is published and occuring. The equation really changes when you look at the near term versus the long term.

I also think it's helpful to move away from the notion of preserving things forever. It seems more helpful to say "my organisation will take responsibility for preserving this for 20 years. After 15 years we will reassess if we keep it; whether the responsibility will transfer to another party; or whether perhaps we discard it at the end of the period". This is a much more structured kind of thing than just saying we'll keep it forever. These more realistic timescales are probably a very good way to structure arguments about preserving items in repositories right now.

Repositories in the bigger economic environment

I note a couple of things. Firstly I have a feeling that we have to get a lot more serious about the idea of "do what you can with bulk ingest now and deal with it later". There are a lot of materials coming at us now that we are not prepared for. We have to do our best to take them in and pass them on. In the current economic climate corporations of long historical status are evaporating and some sort of memory organisation needs to take on their corporate records and archives. At least in the states some government records - especially at local levels - are in peril and we have to think about sudden onslaughts of material not covered by "give us £50 million pounds for this work" and that instead need instant very low cost action.

I'm struck by the question of the extent to which we are trying to market services to a user community rather than promoting collections created by the services. I think we present both sides of that in a confusiong way. Are we doing something for our users as the service or is the value in the resultant collection? I think that ties closely to mandates for research data and open access - they favour the service side. But there is also the every popular critique that "I looked in your repository and there's really nothing interesting there".

There is a thought I'd like to share that at the rate that the economic structure of scholarly communications is changing, and given the kinds of economic pressures at some institutions, repositories at the instititional or disciplinary level, may take on far more importance far more quickly than we imagined: they may become the main access route to scholarly information. Given serials budgets and the pressures to channel money into data curation I can see a time when repositories are a primary - not a supplementary - access path to scholarly materials.

I will close with two fringey propositons.

The first I have been thinking about on and off for a couple of years. About how to make the case for repositories at an institutional level. It may be wrong to think of lots of transitional deposits, it may be that departments interact with repositories infrequently but on a big scale. Suppose we set up a programme for a distinguished academic so that we sent someone to collect scholarly materials and move copies of those into the repository in an orderly fashion creating a legacy of material from the subject honouring their work. I think that would be very attractive to scholars and could be seen as a real way to honour individuals and highlight institutional achievement. This may be a better way to gain support for a repository than chasing everyone for every paper.

The first I have been thinking about on and off for a couple of years. About how to make the case for repositories at an institutional level. It may be wrong to think of lots of transitional deposits, it may be that departments interact with repositories infrequently but on a big scale. Suppose we set up a programme for a distinguished academic so that we sent someone to collect scholarly materials and move copies of those into the repository in an orderly fashion creating a legacy of material from the subject honouring their work. I think that would be very attractive to scholars and could be seen as a real way to honour individuals and highlight institutional achievement. This may be a better way to gain support for a repository than chasing everyone for every paper.Secondly IRs need to move from just being for academia and research centres. A public variation, perhaps local repositories or interest based repositories which may be separate to the academy but may connect in some ways, and we need to think about how we connect to those and build integrated access to information that has scholarly impact for the long term. As well as making scholarly materials more available to the wider public.

I throw these ideas out for the future.

Its very striking how much progress has been made with repository deployment. The software still has rough edges, deployment strategy has rough edges but I come away from discussions like this with the feeling that there is very substantial momentum. And we need to use that wisely especially when we think about where to put investment effort into repositories I think that trying to do everything will dissipate momentum but there is enough momentum that many things are achievable at this point.

And I think that's where I should finish.

Q & A

After an enthusiastic response from the audience Peter Burnhill reflects on Cliff's talk. This is the second repository fringe - they are supposed not to be too formal. Peter asks that when we all blog about this event we should think about what is or is not working at these events. The idea we have is that we try new things and see how things can change etc. So on that note, how do we start the questioning? There are so many threads here to explore - we'll be teasing some of these out at the pub later I think but lets get that started here...

Q (Sheila Cannell): On the economic point, at the moment repositories are very tied up with scholarly economics and the relationships with publishers. How could the economic crisis lead to a sudden change? I can't quite see how this would happen. My fear is that we continue with a number of models not knowing what we should be doing.

A (Cliff): I think it's unlikely to change for all disciplines at once or in the same way. I am struck by just how bad the economic situation is in the states. There have been huge cuts to the library budgets. I live in California and the library and University financial cuts are astounding at the moment. I can't imagine getting to a point in a few years where you might ask the high energy physics folks if they could pay for the physics archive or if they would rather keep the journal subscriptions. They'd obviously prefer both but pushed they'd probably go for the archive. Second tier journals will fall off subscriptions lists but from time to time they publish important articles and these become invisible if not accessible some other way. I'd like to think we'll see an explosion of overlay journals cherry picking from the content in IRs but I'm pretty sceptical about that at this point. My personal, and rather unpopular, view is that we will back off a lot on peer review in a lot of disciplines. I think the biomedical sciences will hang onto it but I think we have been profligate in using unneccassary manpower and increasingly the systems just don't work properly. We're not being strategic enough about where we do peer review and where we don't. My guess is that you'll see more direct distribution of scholarship through repositories or reconstituted university press organisations rolled into libraries than you've seen in the past.

Q (Ian Stuart): You had a comment on the peer review process. Is it the concept or the method that you think causes the problem?

A: There is a bunch of problems: the volume of literature; the person hours in the process; the tendency to send stuff out for peer review even when it is oviously trash or not good candidate work; there is a culture of materials being submitted, rejected and submitted for the next tier journals so the same piece of work is reviewed multiple times. Can we afford these processes? If people did their fair share of peer review it would be something like 8 weeks per year out of someone's productivity.

Q (Les Carr): I was initially horrified by the idea that you think of the repository as a place to store work at the end of careers - a mausaleum concept crept into my head - but you could equally talk about the other end of careers and the proof of your value when trying to get tenure. Perhaps using repositories as the way to show the value of contribution is what I will take away to think aout.

Q (Les Carr): I was initially horrified by the idea that you think of the repository as a place to store work at the end of careers - a mausaleum concept crept into my head - but you could equally talk about the other end of careers and the proof of your value when trying to get tenure. Perhaps using repositories as the way to show the value of contribution is what I will take away to think aout.A: I think your choice of the tenure review as a potential intervention point is a really interesting one. At a well run institution you marshall transactional work, you not only look at your publications but you also talk about what you see hapenning in the future and you could represent that in a repository in a very useful way. You could even move tenure cases into the repository too. It is a really interesting idea.

Comment (Peter Burnhill): Two things you spoke about, archival and appraisal responsibiity are very interesting. And also that it is not just our stuff - neccassarily the repository movement has been concerned with academia, with our stuff but we need to look out to the wider digital world and representation of that for future scholars.

Response (Cliff): I think there is an interesting example here. The Library of Congress put a bunch of pictures on Flickr. What they thought they were doing was seeing if tagging is a useful retrieval mechanism. What was interesting was that they invited people to comment (as well as tag) these photos. These were images of the history of American life - locomotives, airplanes etc. It turns out that there are people around who will tell you the entire history of a locomotive, and the maintenance manual, and the book they wrote on it, etc. just from seeing an imge. When you put up these pictures all that stuff comes into play as surrounding documentation. We don't have a good place to house that right now. This is stuff of schizophrenic scholarly use. Scholars aren't much interested until it is useful for their research some how. I think there's some really interesting stuff to look at here.

And with that further food for thought Peter closed the questioning there by thanking Cliff for an excellent summary of his excellent keynote.

And with that further food for thought Peter closed the questioning there by thanking Cliff for an excellent summary of his excellent keynote.And finally Peter handed over to Ian Stuart for the results of the Grand Challenge which took place earlier today.

Ian Stuart (EDINA), Balviar Notay (JISC) and Ben O'Steen (Oxford University Library Services) were the judging panel. There were 4 very different submissions.

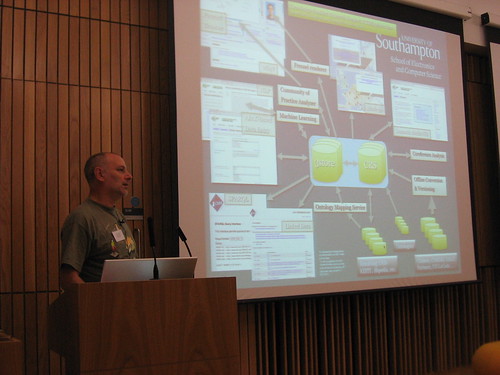

Ian Stuart (EDINA), Balviar Notay (JISC) and Ben O'Steen (Oxford University Library Services) were the judging panel. There were 4 very different submissions.The question asked for enhancements for a repository for the interest of the researcher. After much discussion we really liked what Patrick McSweeny had done. Basically it was a mash-up of information from the e-print repository and his university website and managed to produce a single information page about a specific researcher which was automatically kept up to date.

Congratulations Patrick!

And with that the 2009 Repository Fringe draws to a close.